|

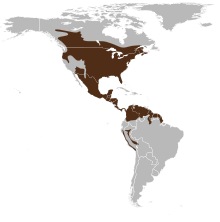

White Tailed Deer Order: Artiodactyla Family: Cervidae Genus: Odocoileus Species: O. Virginianis Deer

appear in paleolithic cave paintings at Altamira,

on the north coast of Spain, going back 36,000 years. The white tailed

deer has

been in North America for about 4 million years, making the white tail

one of

the real veterans of nearly all varying habitats in North America,

ranging from

Nova Scotia west to southern Alberta, sweeping south into Central

America, with

gaps west of the Rockies. To put that in perspective, modern moose,

alces

alces, have only been in North America about 15,000 years, having

migrated

through Berengia about the same time the ancestors of native Americans

began to trickle across. In

North America, moose

have much more serious problems with winter

ticks in affected habitats than deer have. For example, deer go through

winter with an average of about 300 winter ticks, while moose may

accumulate from 10,000 to 90,000 winter ticks, a condition which has

moose in trouble all along the US-Canadian border from Maine to

Minnesota. Are white tails simply more efficient groomers, or could

there be

a connection related to longevity in habitat, and the ability of

animals to

adapt to parasites and challenges not found in previous habitats? Deer

have played a major role in human nutrition and

survival for a very long time. European immigrants to America, learned

from

native Americans about utilizing all parts of the white tail. Deer

numbers rose

and fell in the 19th century with market hunting by both

native

Americans and the growing numbers of settlers and immigrants, joining

individual hunting, along with deforestation and destruction of deer

habitat.

State regulation of hunting slowed down the hunting free-for-all, and

helped

increase deer numbers, but two other factors in the first decades of

the 20th

century led to an explosion of deer. Everything

in nature is connected. The increasing

suburbanization and the expansion of farming in America had the effect

of moving

more people into deer habitat, while introducing deer to our orchards,

crops

and gardens, thereby increasing their ability to making a living and

reproduce.

The more deer saw, heard and smelled human activity, without being shot

at,

the more it helped to inure them to the dangers of our presence. In

an environment without humans, gray wolves tend to

be the number one controller of both deer and western coyotes, the

latter in

competition for safer prey, smaller than moose, elk and bison, but the

accelerating persecution of gray wolves, which included poisoning

campaigns and

bounties led to an explosion of both deer and coyotes. Predators tend

to strengthen the health of prey populations by detecting and

eliminating disease and weakness. As

wolf habitat in the lower 48 dwindled to Minnesota,

the only state which kept the Federal wolfers out, western coyote

numbers

exploded out west, leading to a manifest destiny in reverse, with

coyotes

increasingly moving east under and over the Great Lakes,

exploiting available wolf habitat in the

lower 48, and causing further hybridization of Algonquin wolves in

Ontario and

Quebec, already averaging 20% western coyote going back tens of

thousands of

years, long before there were any humans in North America. Yes,

you read that correctly. Wolves have the most dangerous job in nature

for two reasons. An alpha female may deliver 4 to 7 pups every Spring.

While it is much safer for wolves to go after deer, snowshoe hare and

beaver, pressure to produce food compels wolves to go after much

larger, more dangerous prey, such as moose, elk and bison. Moose, for

example, are so dangerous in defending themselves, that wolves test 20

moose for each one they decide to take a chance and attack. As though

that factor in intself didn't make a wolf's life dangerous enough, in

wolf economics, the pack has to defend a territory large enough to

contain enough prey for the pack to make a living, and if a neighboring

pack's territory is not producing, they'll be invading another pack's

territory, which will result in wolves killing each other over access

to prey. Add these factors to our inclination to shoot wolves, and

wolves are lucky to reach their fifth birthday in the wild. Gray

wolves tend to kill coyotes, just as coyotes kill fox, routinely and

opportunistically eliminating the smaller predator, as a means of

creating a larger base of smaller, safer prey, but

starting in

Minnesota and heading east over Lake Superior, young male wolves, who

“disperse” from, in other words, leave Mom and Dad’s territory,

to seek an unguarded territory, or

a territory they may be able to take over, may discover that female

wolves

don’t generally disperse as far as males, so they may end up defending

a territory

no other wolf wants, and they may end up mating with a female coyote. Deer

hunters tend to bemoan the impact of eastern

coydogs, more accurately termed coywolves, because of their

hybridization with

Algonquin wolves, on the deer population in the Northeast. But the

coyote

impact on deer numbers is much greater on fawns than it is on adults,

partly

thanks to our assistance with traffic accidents supplying deer as

roadkill. A

study by SUNY College of Environmental Science

&

Forestry a few years back concluded that, excluding fawns, 92%

of deer

eaten by coyotes in New York were killed by cars. About 60% of fawns

reach

maturity, while

80% of fawn mortality is caused by predators, including bears, wolves,

coyotes,

cougars, bobcats, lynx, fishers, eagles, and even foxes. Other fawn

mortality

factors range from car accidents to getting caught in fencing or under

farm

equipment, or natural causes like starvation and drowning. More

recently, hunting generally, and deer hunting in

particular, which peaked among baby boomers in 1982, while rising in

some

states, and falling in others, is in a fairly steady decline

nationwide. We've

lost 10% of all hunters in the last ten years, with less than 4% of

Americans

involved in hunting today, at exactly a time when, having largely

eliminated

wolves, nature’s tool for deer control, we need more human hunters to

control

deer numbers. For those concerned about health and red meat, venison is

much

leaner than beef, and probably half the calories. Controlling deer without natural predators

is no easy problem. Highest deer densities are often found in

thickly settled suburban areas, where it is unsafe, and often

illegal, to fire rifles or shoot arrows, and the deer take a heavy toll

on gardens and landscaping generally. Some towns and villages are

experimenting with immunocontraception, to cut down the number of does

breeding. Such methods may require multiple doses, and may only be good

for a couple of years. Other towns employ specially vetted deer hunters

to control local deer populations. Habitat carrying capacities, which

increase as deer learn how to eat more human planted and invasive

vegetation, determine how many deer a particular area can support,

which means as you eliminate deer, other deer come in from surrounding

areas. In

New York State, we have just under a million deer, with

60 to 70 thousand in the Adirondacks, and about 70,000 vehicle deer

collisions statewide

annually. Hunters took about 225,000 deer in New York State in 2018. As

elegant

and visually appealing as white tails are, their lives tend to be

violent and

short, with the average age of death for deer being about 3 years old.

As a

sign of the times, the mosquito, which for 80 years was the most likely

animal to

be involved in human mortality in the lower 48 states, just as it is in

most

moderately temperate countries, was knocked out of first place by the

white

tailed deer, because of the number of people killed in accidents

involving

deer. Following

Bergman’s Rule, white

tails in colder climates will be larger on average than deer in warmer

climates, as

larger deer in colder climates are more likely to survive cold winters,

thus

surviving to breed and pass along their genes for superior size. While deer flourish in widely varying

habitat, ideal habitat tends to be woodlands, river valleys, forest

edge,

swamp, meadow and farmlands. The Adirondacks, with its rough

mountainous

terrain,

is not good habitat, and most of the hunters who hunt in the

Adirondacks are here

as much for the beauty and splendor of an Adirondack Autumn, and would

more

likely

find more deer in their back yards or local forest, than they will up

here. Adirondack

bucks average about 200 lbs, with mature females at about 160 lbs. Deer

are mainly browsers, feeding on leaves, shoots,

woody stems, shrubs, bushes or fruits. They also consume large

quantities of

forbs, mainly broad leaved, flowering plants, which are not grasses,

sedges or

rushes. Some grasses are grazed, along with some lichens and mosses.

But deer

are also opportunistic and will eat bird’s eggs, and even nestlings.

Food

proportions change season to season, based on availability, and while

there is

no season in which browse is not their main source of food, the highest

percentage

of browse is consumed in the winter, while the highest percentage of

forbs are

consumed in Spring and Summer. Special circumstances like nursing does,

rutting

bucks, etc. require higher quantities of food. Mature deer eat about

five to

seven pound of vegetation a day. Bucks

spend a great deal of nutrition growing those impressive antlers, which

begin to sprout in April, and are quite sensitive,

as they

are covered in a fuzzy skin called “velvet”, which contains nerves to

keep the

buck aware of physical obstacles in the immediate surrounding of the

growing

and vulnerable antlers, and blood vessels to feed oxygen to the

antlers, which consist

of cartilage, and two types of bone. The cells of interior “spongy”

bones

enable the inflow of nutrition and growth regulating hormones, and the

hardened

bones which make up the exterior of the antler, and whose gradual

thickening

will serve as the main weapons in the jousting and pushing of the rut. As

the antlers reach full size in August, the velvet

covering the hardened antlers dies and dries, and is sloughed off by

bushes,

tree branches and gravity. Like boxers in training camp, the bucks

begin to

spar with each other in preparation for the rut. As with bull moose,

large,

experienced bucks will spar playfully with youngsters preparing for

their first

rut. As they approach the November rut, buck necks thicken, preparing

for the

impact of serious fighting. The number and size of the tines on the

antlers not

only attract deer trophy hunters, but also signal the bucks readiness

for the

rut, and their desirability as mating partners to does. White

tail mating season in the Adirondacks peaks in

early November. Does go into estrus during this period, but are only

receptive

for about 24 hours at a time. What triggers estrus is not entirely

clear, but

most research cites a “photoperiod” meaning length of daylight, which

would

explain why estrus periods vary from climate to climate, with latitude

the most

important factor in providing the photoperiod. Does

leave hormonal clues, mainly melatonin, announcing

their condition as they move around, and aroused bucks follow these

scents,

often sparring with other bucks, for the right to mate with does, when

the does

are receptive, or to stay near the does, waiting for them to come into

heat. Bucks

become so focused on mating, that they will forgo eating. The rut

naturally

weakens them, and local predators like wolves and cougars will exploit

that vulnerability.

Does who

are not impregnated during the main rut, may enter a second estrus

period in

early December, which may lead to a second rut. Like moose, bucks will

drop

their antlers after the rut season is completely over, in the

Adirondacks

usually around New Years. Bucks

who have successfully mated with does, may hang around

the doe until her estrus cycle has ended, to discourage other bucks

from mating

with her. This type of behavior, protecting male semen, is found in a

wide

range of animals, even down to the insect world, where male damsel

flies

actually have a scoop appendage to “scrape” out the semen of other

males who

mate with their intended after they do. While I’m generally very skeptical about any explanation that smacks of teleology, the belief that nature has a purpose which manifests itself above and beyond the actions of individuals within a species, often used as a proof of a creator or intelligence which guides what happens in nature, this is indeed a fascinating observation. I’ve

always scoffed at the notion that the buck mounts

the receptive doe in order to insure the continuation of his genes,

rather than

just his compulsion to have sex because it is pleasurable, but here is

one

argument in favor, in as much as the intricacies of intercourse from

“foreplay”

to consummation do in fact lead to the continuance of your genes in the

gene

pool. And it doesn’t always work, as it is not uncommon for two sibling

fawns to

have different fathers. The

same thing happens in bear litters. Bear sows may mate

with a third boar, even as two other boars are battling to determine

mating

rights to their unfaithful sow. Someone should tell bucks and boars

that

fighting over the right to mate with their intended, may be less

productive

than just running around and mating with as many as you can! This

is the most productive time of year for the deer

hunters, but it is also unfortunately the most likely season for car

accidents,

as aroused bucks are even less careful near roads than they normally

would be, and

encounter unwary drivers who may be focused on the upcoming holiday

seasons. While

a doe can mate at only seven months old, most

bucks and does generally mate for the first time during their second

year. The doe’s

gestation period is about six and a half months Mature does commonly

give birth

to a litter of two fawns, while first year mothers usually have a

single fawn.

Mom will encourage a newborn fawn to stand and nurse within 20 minutes

of birth,

and will lead it to tall brush or grass, where it should be safe from

predators, while Mom forages to generate a milk supply for the fawn. Deer

fawns, as well as moose and elk calves, have less

odor than one would expect, because predators, over thousands of years

of

predation on them, inadvertently weed out the “stinkier” prey, leaving

the

surviving fawns and calves to survive and breed, passing along the

genes for

less odor. This makes the doe’s strategy of hiding her fawn in tall

grass and

brush a sensible solution, as they are not as likely to be smelled by

patrolling predators, unless they are stepped on by the predator. Folks

encounter fawns who are lying down, call us at the Wildlife Refuge to

report

there is something wrong with the fawn, because it makes no attempt to

escape.

We respond that the fawn is just doing its job, and you should clear

out, as

you may be noticed by mom, and the last thing we want is for her to

abandon her

fawn. Fawns

suckle mom for the first three months, will lose

their spots in the Fall, and will stay with Mom, usually through the

first

Winter, until they go out on their own the following Spring. Deer molt

their

coats twice a year, having tawnier, deeper tone coats in the Spring,

and

grayer, duller coats as camouflage for the Winter.

Steve Hall |

White tailed deer by Joe Kostoss, Eye in the Park

White tailed fawn and Doe, by Joe Kostoss, Eye in the Park

White tailed deer in Winter, by Joe Kostoss, Eye in the Park

| Home |

Release of

Rehabbed Animals |

Learn

About Adirondack & Ambassador Wildlife |

Critter

Cams & Favorite Videos |

History

of Cree & the Adirondack Wildlife Refuge |