|

Porcupine Order: Rodentia Family: Erethizontidae Genus: Erethizon North

American porcupines are large

rodents whose ancestors apparently crossed from Africa to South America

on

floating trees and logs 30 million years ago, and whose most prominent

feature

are the approximately 30,000 quills which grow everywhere individually

out of

the skin musculature, interspersed with bristles, under fur and hair.

The

quills defend the porcupine from attacks by predators, and the only

areas quill

free are the face and underside. This may explain why porcupines are so

often

hit by cars, as their general experience is that larger animals will

avoid

them. The

word porcupine comes from the

old french word porcespin, which roughly translates as thorn

pig. While

there are 58 species of new and old world porcupines, distibuted over

two

different families. our north american version may reach two and a half

feet in

length, with their rotund bodies weighing up to 40 lbs, making them

second to

the beaver as the largest rodent in North America. Porcupines

prefer coniferous and

deciduous forests, with food rich understories, and can live into their

late twenties.

They do not hibernate, but may share wintering quarters with other

porcupines,

in caves, covered depressions, hollowed out logs and trees, etc..

Porcupines

are mostly nocturnal herbivores, eating mainly greens like herbs,

clover and

skunk cabbage during the growing months, while spending much of their

time in

trees in winter, eating tree bark and evergreen needles, while getting

minerals

by chewing on antler sheds. Like

many mammals, they need sodium,

and may be attracted to anything which has been coated with human

sweat, from

wood handled tools and paddles to outhouse toilet seats, or even

anything that

has been peed on, as our urine contains a high sodium content. They’re

also

attracted to the sodium components found in building materials, such as

plywood. Porcupine

mating is generally in

late Summer, and the mating rituals are as strange as the porcupine’s

general

appearance. Females are only sexually receptive from eight to twelve

hours,

once a year, making foreplay and competition among males an urgent

process

indeed! The male does a rather ornate dance, which includes

vocalizations and spraying

urine over the head of the female. Seven

months later, in early Spring,

mom gives birth to a single baby, whose quills are thankfully soft as

they

emerge from the womb, hardening within hours, and within a few days,

the young

one is already foraging, and will stay with Mom for about six months.

Porcupines have a wide vocal range, which includes grunts, shrieks,

wails,

coughs and tooth clicking. Our own

ambassador porcupine,

Shmendrick, seems to whine and moan in pleasure when he eats watermelon

and

butternut squash. Shmendrick was raised at the Refuge after his mom was

killed

by a car, a common fate, as porcupines figure most moving critters will

sensibly avoid them. Shmendrick was released back into the wild several

years

ago, with instructions to go get a job, and then, to our astonishment,

came

back after about two years. We do have many wild porcupines living

within the

Refuge’s 60 acres, but maybe Shmen missed the easy old days of not

having to

provide his own chow. Porcupines

have claws well suited

for climbing, while their hollow quills enable efficient swimming. The

quills themselves

are principally modified hair, coated with keratin, a fibrous

structural

protein which is a main component of hair, fingernails, claws, horns,

etc. The

quills come in a variety of length, thickness and pattern, with the

longest

being on the rump, with the business end of the hollow shaft featuring

a sealed

barbed terminus, making the quills very hard to remove, when the air

tight

quills are warmed by the sun, as well as the skin of the unfortunate

recipient. Porcupines

are attracted to buds on

tree branches and stems which may not handle their weight, so falling

out of

trees is a common porcupine fate. Fortunately, their skin contains

antibiotics,

useful in the event the porcupine quills itself, by falling out of a

tree, or

when males fight during the mating season. Porcupines,

like other predator

targets, would prefer disengagement to fighting, and employ both

audible and

visual cues to warn would be attackers. These include teeth clattering,

turning

its back to display the quilled tail, which may be lashed at the

attacker,

arching the back to make the quills stand up, and shivering to cause

the quills

to rattle and wave menacingly. As with actual contact with the

attacker, the

latter activity may cause some quills to shake loose and fall, which

may be

behind the popular folklore that porcupines can shoot their quills.

They can’t.

Like possums, porcupines can emit a really offensive odor when

frightened or

agitated, in their case, from skin glands called rosette on the lower

back. A

relaxed porcupine can be gently stroked, starting at the head, but

don’t try

this at home. If your

dog gets quilled, and you

can’t pony up the likely expensive vet bill, and you have one seriously

patient

and trusting dog, you can sever the quills midway, to let the air

escape, and

gently twist and pull the embedded remains of the quill. While

porcupines are obviously very

risky targets for predators, they are effectively attacked by cougars,

who may

knock the porcupine out of the tree, somewhat less by great horned owls

and

eagles, and painfully by bears, wolves and coyotes. The porcupine’s

main enemy

is the fisher, whose numbers continue to grow in much of New York

State, as

porcupines increase their numbers and range. Steve Hall |

Adirondack Albino Porcupine by David Plumley

Porcupine, Denali National Park, 2012 by Steve Hall

Wiki - http://www.nhptv.org/natureworks/porcupine.htm#2 - Wiki

Porcupine Quills - Porcupine Range - Porcupine Prints

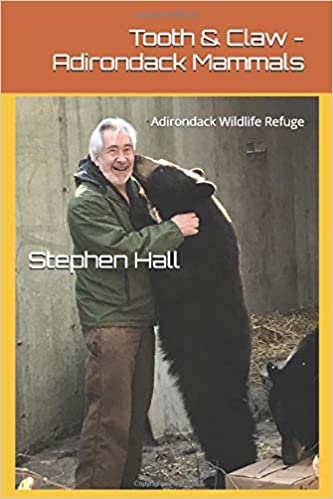

Come meet our Ambassador Bears & Learn all about Bears

| Home |

Release of

Rehabbed Animals |

Learn

About Adirondack & Ambassador Wildlife |

Critter

Cams & Favorite Videos |

History

of Cree & the Adirondack Wildlife Refuge |